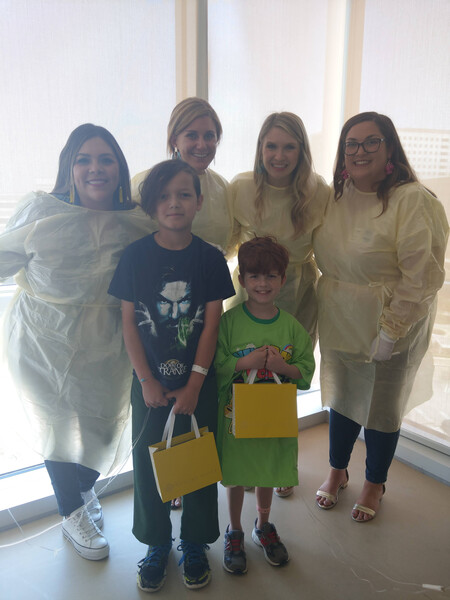

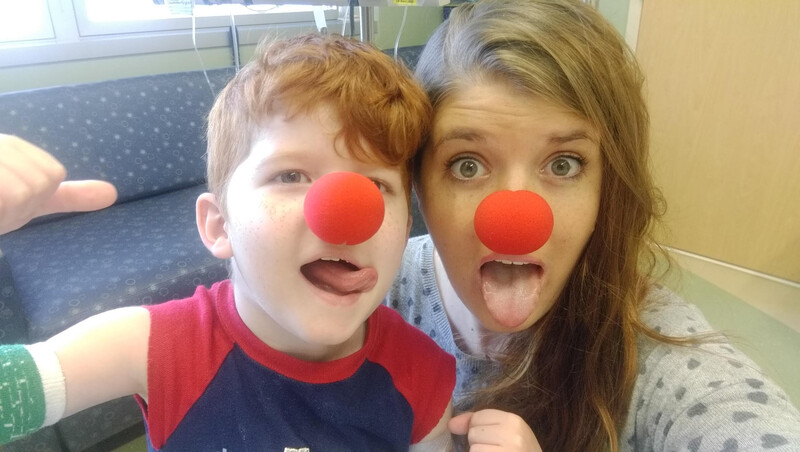

Tanner and Caleb

Brothers Tanner and Caleb are like a lot of siblings. They tease and fight - all in good natured brotherly love. And they're also each other's biggest defenders.

Caleb smacked the palm of his hand and raised it in the air toward his older brother’s face.

“You see this?” he said, pointing to his outstretched hand.

His 12-year-old face was serious – too serious. You could tell he was struggling to hold back a grin.

“It’s going to become your worst nightmare.”

15-year-old Tanner was quick with a spar back.

“What? Your pinky finger,” he said, chuckling, before flicking Caleb behind the ear.

Brothers Tanner, 15, and Caleb, 12, are like a lot of siblings. They tease and fight – all in good natured brotherly love.

And they’re also each other’s biggest defenders.

Both born with the genetic disease, cystic fibrosis, Tanner and Caleb are close – even when their disease requires them sometimes to be six feet apart.

“It’s that brother relationship that I can hit him, but if anybody else does, I’m hitting them twice as hard,” Tanner said. “I’m the older brother. I watch out for him.”

Cystic fibrosis – often shortened to CF – is a disease that causes severe damage to the lungs, digestive system and other organs in the body. Patients often are required to stay six feet away from others with CF to prevent the spreading of germs, which can be difficult to treat and lead to a faster decline in lung function.

But for Tanner and Caleb, they’re only kept apart when they are sick.

Otherwise, they spend time doing brotherly things like gaming, rollerblading and playing baseball.

There’s currently no cure for CF, and that means the brothers spend hours each day working to live with their disease.

There are daily breathing treatments, which they usually spend wrapped under fuzzy blankets on the couch together watching a movie on high volume, as machines whir in the background and a vibrating vest shakes mucus from their lungs and opens their airways.

And there are dozens of pills – more than 30 for Caleb – that they take every day before meals to help them digest their food.

“He has to take the pills one at a time,” said Tanner, who can swallow a handful at once, jokingly.

“No, I take two at a time now,” Caleb replied in defense. (He’d been practicing for the last year so he could spend less time in the school nurse’s office each day and more time with his friends.)

“Most kids can play all day, but I have to go inside and do breathing treatments and take pills before I can eat,” said Caleb, who has been admitted to the hospital more than a dozen times and has a collapsed left lung. Tanner has had about 30 hospitalizations.

CF makes me feel different. I stand out. In P.E., we have to run a mile every month, and I’m usually the last person to finish.

— Caleb

Initially, Tanner and Caleb’s parents, Stephen and Kiri, were told that most children with CF die very young – even in elementary school.

Knowing they may have limited time with their children, they made a pact to live life differently from their friends and family.

They don’t make plans for more than two weeks out. They travel across the country with their boys, taking them to New York to climb the Statue of Liberty; to both coasts to swim in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans; and to the wilderness to backwoods camp in Yellowstone and Yosemite national parks.

They want their children to see as much of the world as possible – even if their disease makes it challenging to climb to the top.

“We didn’t ever want to say that we let CF hold them back,” Kiri said. “We made sure that we did everything in spite of CF.”

***

About a decade ago, the family relocated to North Texas for the boys to be treated at Children’s Health, after doctors at a previous hospital told their parents that they had exhausted their options to help then-5-year-old Tanner.

“Instead of prepping for the end of Tanner’s life, we visited other hospitals and landed on Children’s Health because it is ranked highly for treating cystic fibrosis,” Kiri said. “Instantly, Tanner started to get better.”

The Claude Prestidge Cystic Fibrosis Center at Children’s Health is a leader in the care of pediatric cystic fibrosis patients, caring for more than 300 children each year in North Texas. The center incorporates a multidisciplinary approach to treating CF patients, providing families access to the best care possible, including cutting-edge treatments and clinical trials.

“When Tanner and his family came to us, they wanted to fight, and we wanted to fight alongside them,” said Preeti B. Sharma, M.D., the family’s pediatric pulmonologist and co-director of the Cystic Fibrosis Care Center at UT Southwestern and Children’s Health. “Having access to both a pediatric gastroenterologist and a pediatric pulmonologist, along with a whole team of specialists, was key to moving the bar forward for him to enhance his growth and his pulmonary function.”

Children’s Health participates in the Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutics Development Network, the largest cystic fibrosis clinical trials network in the world. Our affiliation with this network ensures that our patients benefit from the latest drug trials, clinical studies and a wealth of research in cystic fibrosis treatment.

This collaboration means an improvement in patient outcomes, advancing treatments and prognosis for children with cystic fibrosis -- even since Tanner and Caleb were born.

“New treatments have altered the life expectancy for people with cystic fibrosis dramatically. People with CF are living longer, healthier lives,” Dr. Sharma said. “And we wouldn’t have made any of these advances without the support of the community to help fund research and to advance how we care for CF patients.”

In the last decade, these therapies have changed the day-to-day life of many patients, improving their lung function, gastrointestinal symptoms and overall energy. Kids feel better and spend less time sick in the hospital. Many also live to be middle-aged adults.

Despite these advances, there’s still a long road ahead for Tanner and Caleb, who have advanced lung disease and are considering lung transplantation.

But access to high quality health care means Stephen and Kiri are hopeful. They’ve started dreaming of the future – making a high school graduation plan for Tanner, saving for retirement and even buying stocks and bonds.

“We started out thinking that our sons weren’t going to graduate high school, and now they have the possibility to live to age 30 or 40,” Stephen said. “They can live a full life. They can have their own kids. They can have a career. They can go to college. They can do anything they want.”

Read more patient stories like Tanner and Caleb's to learn how Children's Medical Center Foundation impacts the lives of North Texas children.

Choose Children's Health on North Texas Giving Day

Your support on North Texas Giving Day provides better care for children who need it, groundbreaking research and more community resources for kids’ mental health.

Did you enjoy this story?

If you would like to receive an email when new stories like this one are posted to our website, please complete the form below. We won't share your information, and you can unsubscribe any time.