Camille's Story: Student athlete and proud participant in a T1D clinical research study

DIAGNOSIS: Type 1 Diabetes

Camille guards the front of the court and spikes the volleyball over the net. Her parents sit on the edge of their seats, cheering from the sidelines.

“I’m really competitive, and it’s a close game,” said her dad, Chad, during an April volleyball tournament. It was late morning and already Camille’s second game of the day.

As Camille runs back-and-forth on the court and high-fives her teammates, you can hardly notice the tiny device below her shorts that continually monitors her glucose levels, which her mom tracks on her phone.

And you’d never know that tucked underneath her sports bra is a pump delivering insulin into her body to control her blood sugar levels.

Diagnosed three years ago with type 1 diabetes, Camille is an elite volleyball player. The lanky 12-year-old enjoys debate, reading and theater. She wants to be a chemist or pharmacist when she grows up. She’s a tough kid who doesn’t mind swimming in the cold ocean until her lips turn blue.

So when she rapidly lost weight and complained of severe fatigue and extreme thirst, her mom, Olivia, an ICU nurse, was worried. She rushed Camille to an urgent care, while Chad, unable to come inside because of COVID-19 safety precautions, waited in the car.

And when Olivia saw that the glucometer registered Camille’s blood sugar level in the high 400s (average is 70 to 120), she walked outside unable to stop the tears.

“I knew immediately that it was type 1 diabetes, but the thought had never entered my mind,” Olivia said, adding that no one in their family has the condition. “Though people don’t usually die from this disease, you have it for the rest of your life. There’s no cure. It’s constant management of your blood sugar, and I didn’t want that for my child.”

Olivia has a reputation for remaining calm in the most intense of situations. After all, she’s an ICU nurse. But when Chad saw her open the urgent care door in tears, he was worried.

“I knew this was serious. I understood that my child was very ill, and we had to get to the hospital immediately,” he said.

An unexpected change

By the time they arrived at the emergency department, Camille could barely walk from the car into the hospital and kept her eyes closed, even while people spoke to her.

She had developed diabetic ketoacidosis and was nauseous, weak and confused. As clinicians rehydrated her, Olivia and Chad began to gently explain the life-altering diagnosis, which in her case is not genetic. (Doctors later determined Camille’s diabetes likely developed from a virus she was exposed to earlier in life that triggered an autoimmune response, destroying her pancreas and its ability to produce insulin.)

“We wanted to make sure she understood that there’s no time off from this. There are no timeouts. There are no summer vacations. It is something that is ever-present,” Chad said. “Diabetes is something that we, as parents, always must account for. And when Camille gets older, for the rest of her life, it’s something she is always going to have to account for.”

Camille stayed in the hospital for three days, sleeping the first night in the clothes she arrived in. During that time, clinicians educated Camille and her family on diet and glucose monitoring. And looking for a glimmer of hope for a disease that has no cure, Chad began to search online for clinical research studies.

He lucked into finding one for a trial studying a revolutionary medication called teplizumab for children newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. The drug is a monoclonal antibody that holds off destruction of the pancreas with the goal to extend a patient’s “honeymoon” period, meaning they have somewhat normal blood sugar levels for a few more years.

“A lot of research these last few years has been in the management of type 1. We have new pumps and devices, but actual disease treatment and how to mitigate it or prevent another person from getting the disease, we don’t have answers to those questions,” Olivia said. “Imagine being able to stop the disease before it destroys someone’s pancreas. This is the closest thing we have to a cure for type 1.”

Children’s Health ℠ was one of the few locations in the country offering the 18-month-long study, and it would require the family, who lives in San Antonio, to regularly drive five hours to Dallas.

Chad and Olivia discussed the study with Camille, explaining the time commitment; blood draws and infusions; and the chance that she could receive the placebo – not the drug.

“I decided that it could help me and kids like me who aren’t diagnosed yet,” Camille said. “Research helps people’s lives now, and it helps people’s lives in the future. It saves lives, and without research, we don’t have answers to anything.”

Clinical research paves the way

Research helps scientists better understand diseases, chronic conditions and injuries, and can lead to the development of new medicines, treatments or approaches to caring for patients. Each year, there are more than 1,200 active research studies at Children’s Health, with nearly 13,000 patients enrolled. For many of these children, research is their last hope for treatment for their illnesses.

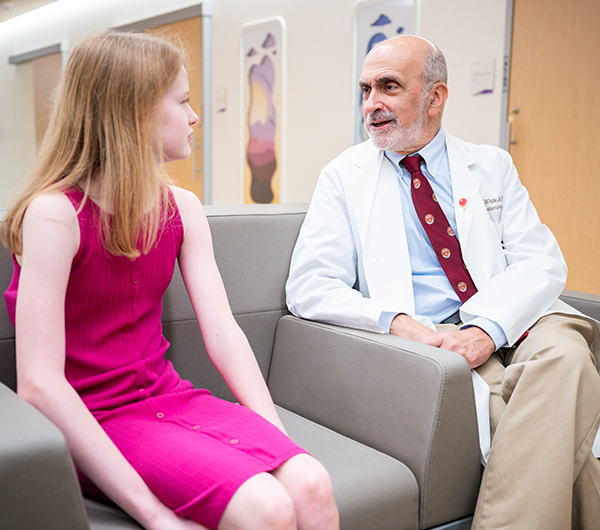

“I’ve been a doctor since 1976, and I’ve seen the evolution of how we practice medicine to create better outcomes for our patients,” said Perrin White, M.D., director of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at Children's Health and professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

“Every single one of those improvements required someone trying something new,” said Dr. White, who also is the principal investigator on Camille’s study. “The single most exciting thing is realizing that you know something, or that you’ve contributed to knowing something that was not previously known. Making my patients’ lives better through research is tremendously rewarding.”

Support from generous donors fuels new areas of research not presently funded by external entities; supports important, life-saving studies that are nationally and locally underfunded; and provides pilot funding that helps researchers successfully apply for larger, future grants such as from the National Institutes of Health.

“Clinical research is extraordinarily expensive because the safety of the participants is our priority. It requires a lot of monitoring, a lot of personnel and very careful procedures. We would not be able to do this kind of research without ongoing philanthropic support,” Dr. White said.

Dr. White said clinical research that Children’s Health patients participated in recently led to FDA approval of a new insulin pump for kids. And he said the team will finish analysis soon on Camille’s study to see if teplizumab was successful in prolonging the honeymoon phase for patients, allowing newly diagnosed kids to have extra time living without diabetes.

“Camille is a very bright, driven girl who is going to make a difference in this world,” said her dad, Chad. “Without the scientific research to help kids who have diseases like type 1 diabetes, some of these kids will not get those opportunities to make a difference and have a future.”

We tracked down five team members, whose faces represent the web of support surrounding Camille's journey at Children’s Health.

These are their stories.

ABHA CHOUDHARY, MD, Pediatric Endocrinologist at Children’s Health and Assistant Professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Co-Principal Investigator for Teplizumab Study

As an endocrinologist, I treat patients with hormone abnormalities. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition often triggered by a virus. It tricks the body into thinking that the pancreas is a foreign gland leading to autoimmune destruction of the pancreas. This leads to insulin hormone deficiency causing high blood sugar.

Currently, there is no cure for diabetes, and it is managed with insulin. It’s a life changing diagnosis. There have been several medical advancements such as continuous glucose monitors and insulin pumps, which have improved the quality of life and outcomes in our patients with diabetes.

That’s where the clinical research piece comes in. It’s amazing how we can perform these research studies, and then apply that to the patient population to improve their treatment and outcomes. Already, Teplizumab is approved for patients who have not yet shown diabetes symptoms for Stage 2 diabetes, delaying the diagnosis. That is a game changer.

Research improves the lives of children, and without donor support, we would not be able to do this kind of work. Research is how we advance science, and we’re extremely grateful to the patients who participate in these trials that allow us to identify new treatments and technology.

YAZMIN MOLINA, Clinical Research Team Lead

I help identify patients like Camille to participate in our clinical research studies. Then, I follow them throughout their clinic visits, monitoring their vitals and outcomes.

I’ve seen drugs that we’ve studied then become approved by the FDA, and it’s incredible to make that kind of a difference in kids’ lives.

Not only are you offering patients new treatments, but you’re advancing medical care. As a hospital, that’s what we’re all about – giving patients access to the best care and the best possible treatments.

MICHELLE MURPHY, Sr. Research RN – Team Lead

I previously worked in primary care and urgent care, where it was all about seeing patients as quickly as possible, before I transitioned to clinical research. When Camille came for her visits, we spent four to six hours together each time, so I got to know her really well. That’s the best part of my job – getting to know the kids and making a difference for their diseases and conditions. The hope with this study is that by administering this medication early on into their diagnosis, it would prolong a type 1 diabetes patient’s honeymoon period, which is a little bit of time that all Type 1 kids have when their pancreas is still producing some insulin. For Camille, she already developed the disease, and we were trying to help her preserve the normal function of her pancreas – or close to normal – for a few years. The most exciting part of research is investigating new drugs that make taking care of these chronic, lifelong issues a little bit easier for patients and their families.

ISRA ROBINSON, IV Therapy

When I was a bedside nurse, I was always able to insert IVs really well, and it was one of my favorite jobs. Now, it’s my entire job. I get to meet so many people, and even though the skill is repetitive, it’s always unique to the individual. There’s an element of challenge to it that I really love.

With research patients, I see them several times when they’re doing infusions for a specific medication and quickly learn their “magic vein.” And we have some different tricks to make the poke painless. Pain management is very important to us because then getting an IV is not scary.

I love helping these kids and being part of the team that is providing them with the treatment they need. Donations are priceless in providing care, especially in this setting. Every little bit helps, and it helps every care team member provide the best care for each patient.

STEPHANIE TIMSAH, Clinical Research RN

Camille just has this very bubbly personality. She was just so much fun. And, the pterodactyl sound? That's kind of what won her over. In the infusion room, there is a picture of a pterodactyl, and we were talking about it at one point, and I was like, ‘I can make a pterodactyl sound,’ and she was like, ‘No, you can't.’ I made the noise, and she ate it up.

Most of the time, these kids interact with a lot of different people, and they're in a very vulnerable position. Breaking the ice with them and letting them know that we are on their team and that we can also be vulnerable says, ‘I'm here with you. I can be silly with you, and I want you to have fun and feel safe.’

The drug that Camille is on has been in the works for years. And now they're potentially going to roll it out and have it available to kids outside of research. Without Camille and kids like her taking a chance with us, then we couldn't bring it to kids in the future.

Read more patient stories like Camille's to learn how Children's Medical Center Foundation impacts the lives of North Texas children.

Kids count on us. We count on you.

Give to support innovative research, lifesaving treatments and compassionate care.

Did you enjoy this story?

If you would like to receive an email when new stories like this one are posted to our website, please complete the form below. We won't share your information, and you can unsubscribe any time.